Risk culture at the heart of adaptation strategies

The South Province auditorium hosted a C’Nature conference dedicated to agriculture and adaptation to climate change on the 2nd December 2025 at 6 p.m. On this occasion, researchers from the CLIPSSA project shared their various works: Catherine Sabinot (anthropologist and ethnoecologist), Maya Leclercq (anthropologist and sociologist, via videoconference from French Polynesia), and Samson Jean-Marie (PhD student in anthropology and geography), as well as Ida Palene, a former intern who is now a civic service volunteer (VSC) in IRD and partially working on with CLIPSSA. Together, they discussed a key question:

How, do farmers observe climate change in their immediate environment, particularly in the South Pacific societies? Do they experiment with concrete responses, and do they pass on knowledge and practices to better adapt to it?

In the Pacific islands, agriculture is practised in close harmony with the seasons, the soil, the winds, the rain… and extreme events. Knowing how to anticipate a very dry period, reorganise crops after heavy rains, or prepare for the approach of a cyclone is part of daily life for many families. At the heart of the discussions is a powerful idea: the communities of New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Wallis and Futuna, and French Polynesia have built, through experience, genuine ‘cultures of risk’. In other words, ways of observing, interpreting and acting that enable them to cope with climate uncertainty. The challenge today is to combine this knowledge and these practices with scientific knowledge in order to strengthen adaptation.

Recognising and identifying vulnerabilities : A real climate threat

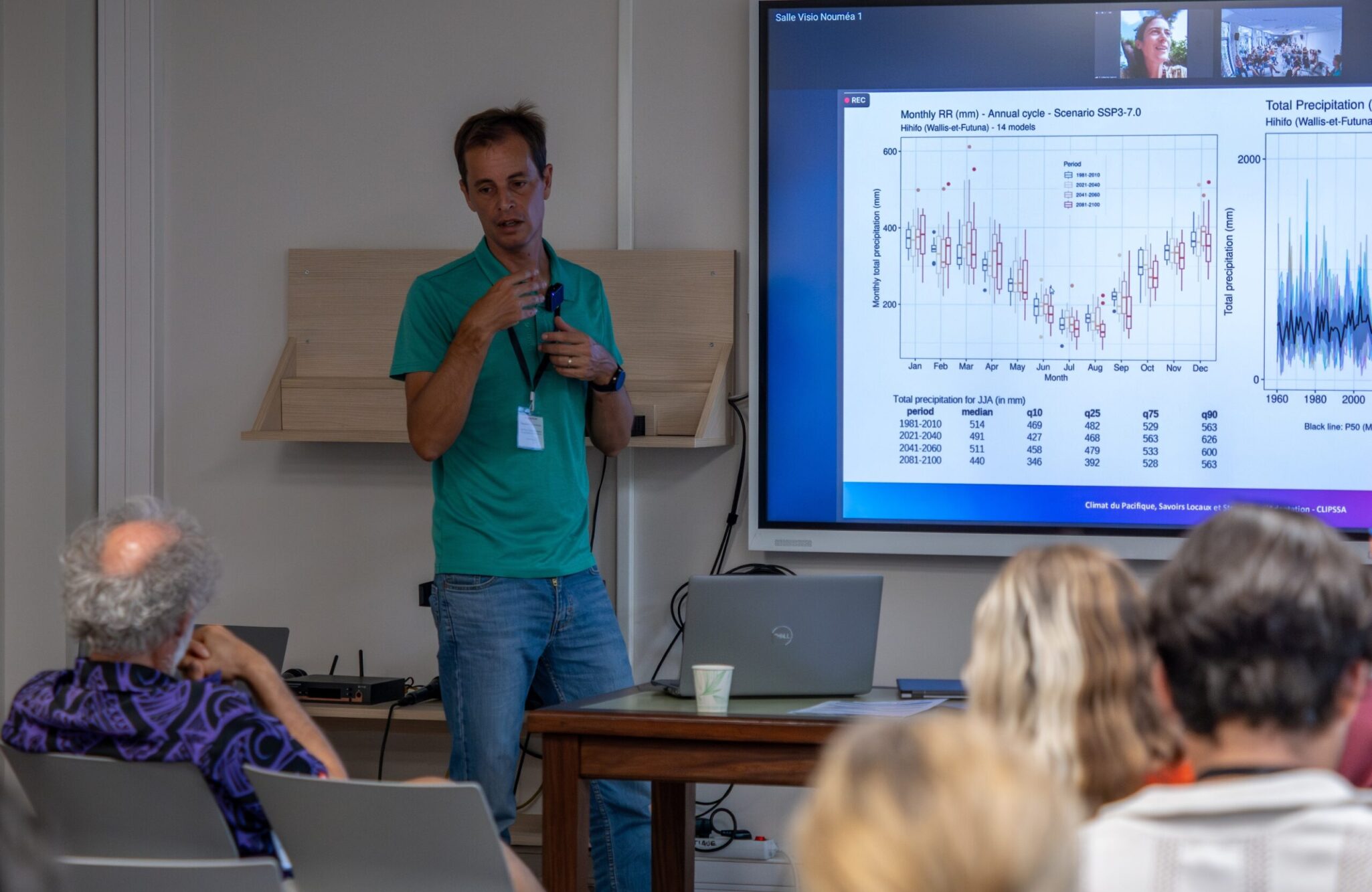

At this conference, researchers highlighted the ENSO climate phenomenon to show that, what farmers are experiencing is the result of a natural process that global warming is altering.

ENSO is an ocean-atmosphere mechanism that can tamper with rainfall and temperature and therefore influence crops, harvests and water storage. Dry seasons are becoming longer and more severe. They impact crop growth, cause water stress, dry up water sources and make the land difficult to cultivate. Conversely, severe flooding leads to disease and drowns crops. In both cases, there are yield losses, food insecurity and arbitrary water management in the face of the climate emergency.

‘The most difficult element to deal with is the water. The dry season lasts longer, and the little creek there (…) rocks, rocks (…) we have to choose which field to save.’ Farmer from Canala, (January 2024)

“When it rains too hard, the mud or soil goes into the sea, and the plants get sick. After these rains, we spend more time repairing than producing.’ Farmer from Vanuatu (2025)

The hybridisation of knowledge : A tool and space for resilience

Hybridisation is an active, living process. It is a combination of endogenous knowledge (which comes from ancestors, is part of genealogy and is passed down from generation to generation) and exogenous knowledge (external sources such as NGOs, science, social media, etc.).

With a real experimental dynamic, it pushes agricultural practices and farmers towards constant adaptation, with improvements and adjustments over time and in response to climatic events.

A variety of actions are being implemented in terms of practices and technical expertise (mulching, slanted stakes, crop diversification, choosing more robust seeds, innovation in irrigation) and expanding space-time (Nakamals, markets, faapus). Social ties are shifting and breaking with convention, societal norms, customs, and traditions are daring to push their boundaries (with the increasing involvement of women, who are often invisible). Adaptation to climate change is happening all around us; it is a process that is set in motion because in Oceanian societies, everything is connected. This holistic vision forges links between inhabitants and the worlds around them.

The tools used by researchers for this hybridisation:

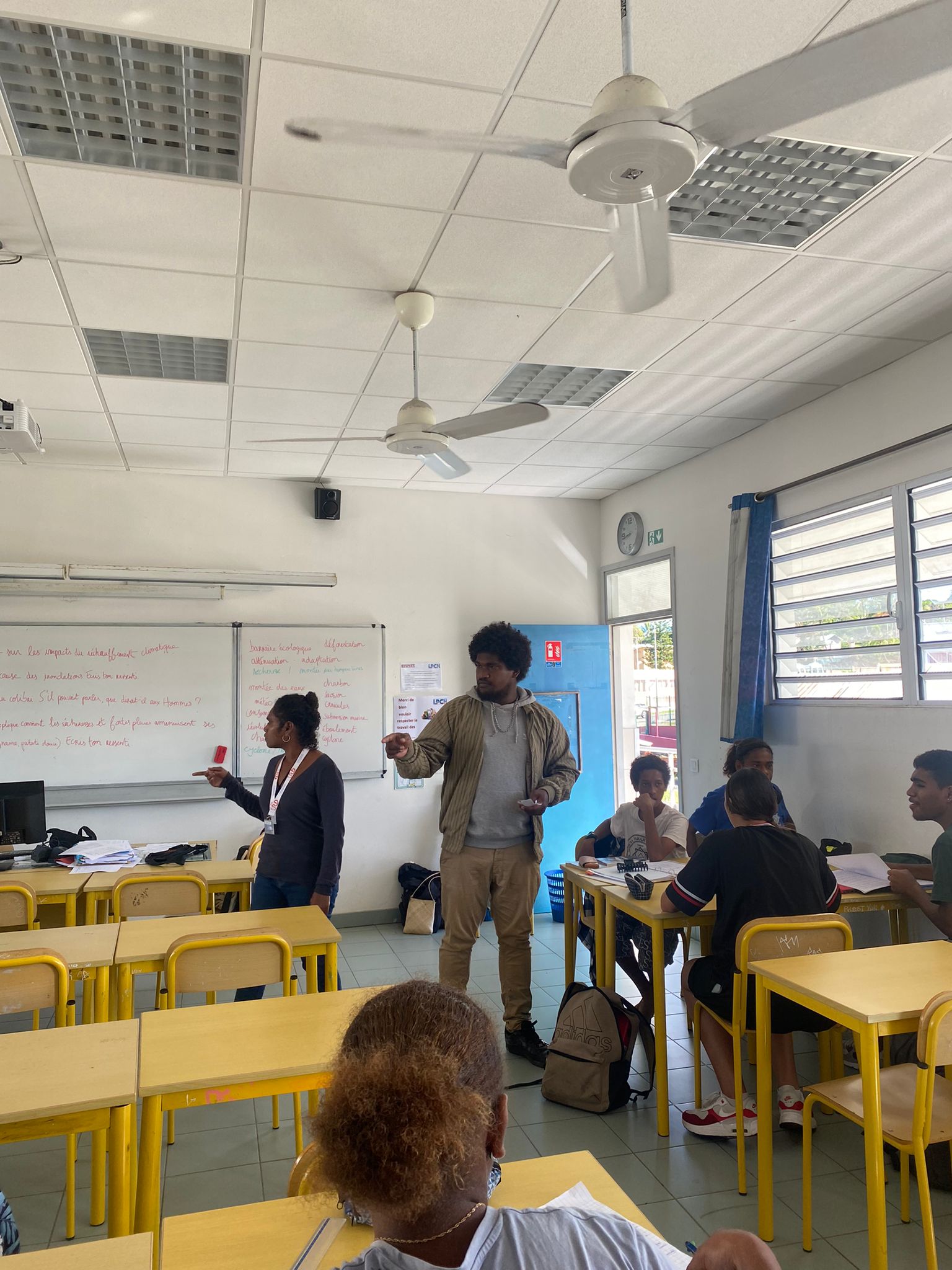

- Co-construction: researchers and the local population analyse climate impacts together (in the field, through interviews and observations) to produce shared knowledge.

- Participatory mapping: spatialisation of areas exposed to cyclones and flooding. Enables identification.

- Artistic workshops and participatory debate: Drawing and representation workshop of the faapu (French Polynesia) multitude of representations, personalisation of space and therefore multiple and specific adaptation to each participant.

As highlighted by the C Nature 2025 conference, these risk cultures must be combined with scientific knowledge. Farmers are on the front line when it comes to dealing with the effects of climate change. By merging endogenous and exogenous local knowledge, we can produce a course of action and adaptive strategies that are more appropriate and co-constructed in line with the realities of those who work the land. These are resources that must be capitalised on, valued and integrated into decision-making.