An international framework for thinking about adaptation

From 13 to 16 October 2025, the CLIPSSA team attended to the Adaptation Future 2025 international conference in Christchurch, New Zealand. Part of the United Nations World Adaptation Science Programme (WASP), this major event brought together researchers, public decision-makers, economic actors, associations and local communities. It provided a unique forum for discussion on adaptation strategies to the effects of climate change, with an emphasis on recognising and using indigenous and local knowledge as levers for resilience. This echoes the areas ofreflection and research-action, the core of CLIPSSA project.

CLIPSSA : A collective and interdisciplinary dynamic

During a panel discussion entitled ‘Connecting knowledge: transdisciplinary approaches to climate change adaptation in the South Pacific’. CLIPSSA researchers demonstrated the relevance of combining exact sciences and local knowledge. These disciplines work together to transform raw data into concrete tools for public decision-making, adapted to the realities of the concerned areas(Vanuatu, New Caledonia, Wallis and Futuna, and French Polynesia).

CLIPSSA operates in a dense institutional landscape, and the project must harmonise the interests of multiple stakeholders (researchers, funders, technicians) at local and regional levels. The cooperation and success of the project, therefore, relies on fluid and clear collaboration between partners with different epistemologies.

‘At the local level, we work with a wide range of stakeholders, each with different timeframes and interests, whether accessing data and results or contributing to public policy direction.’ Fleur VALLET, project engineer and geographer

The humanities and social sciences team: Pillars of resilience

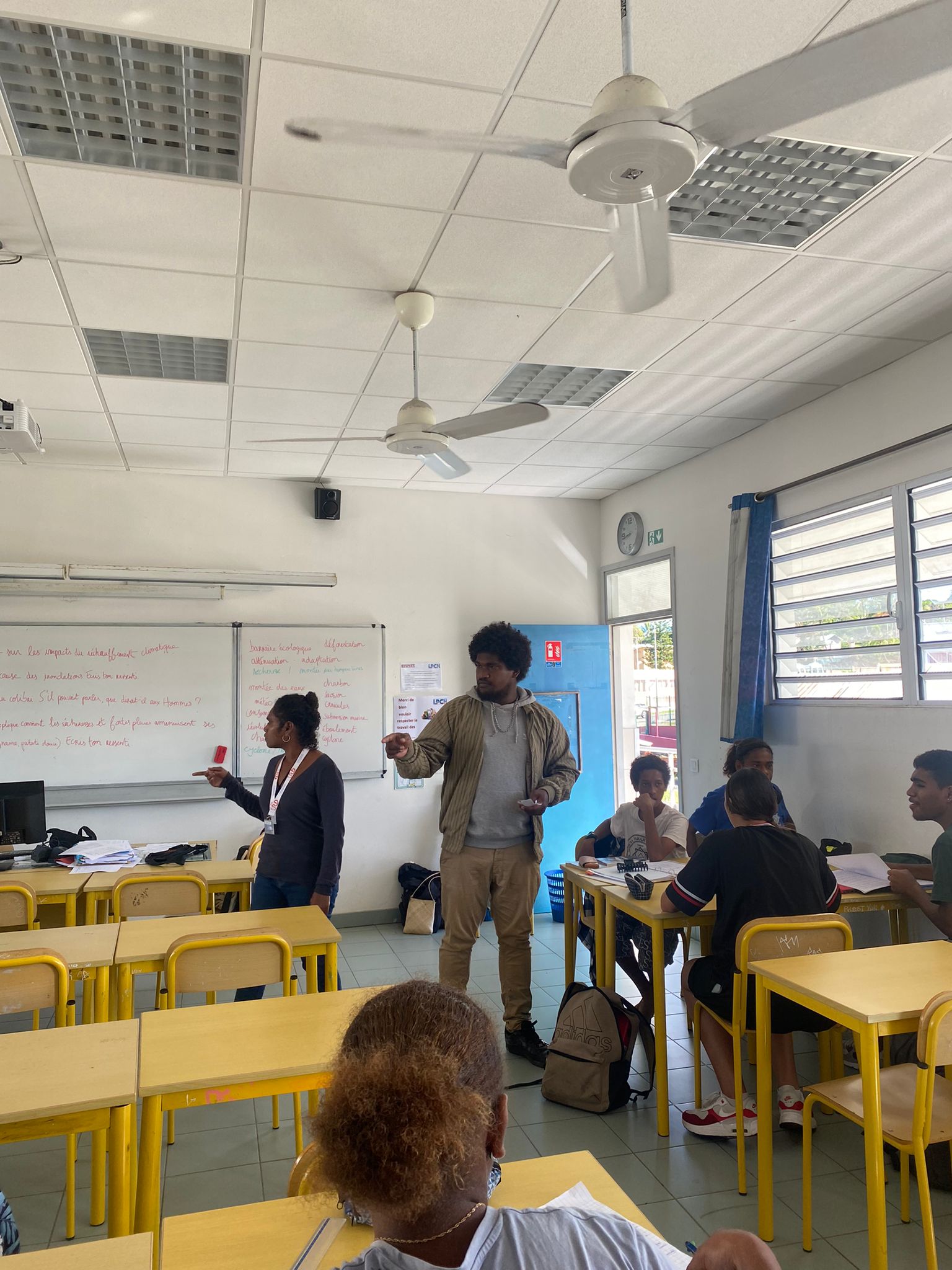

The humanities and social sciences research team (Maya LECLERCQ, postdoctoral researcher in anthropology, and Samson JEAN MARIE, doctoral student in anthropology and geography) demonstrate through surveys and observations that adaptation is the result of practical field intelligence developed by farmers in New Caledonia, Vanuatu and French Polynesia. It stems from a detailed understanding and observation of natural cycles. And although the threats are common (cyclones, floods), the responses are specific to each territory; adaptation is not uniform: it is rooted in local culture and geography and evolves according to context, gender and resources, whether material (agricultural equipment) or immaterial (transmission of endogenous or exogenous knowledge). This illustrates a philosophy of adaptation based on humility and cohesion:

Vanuatu : ‘When the cyclone hits, we don’t decide alone. We get together and see what is still possible.’

New Caledonia: ‘We cannot fight against the water, so we adapt to it.’

From climate modelling to agricultural resilience

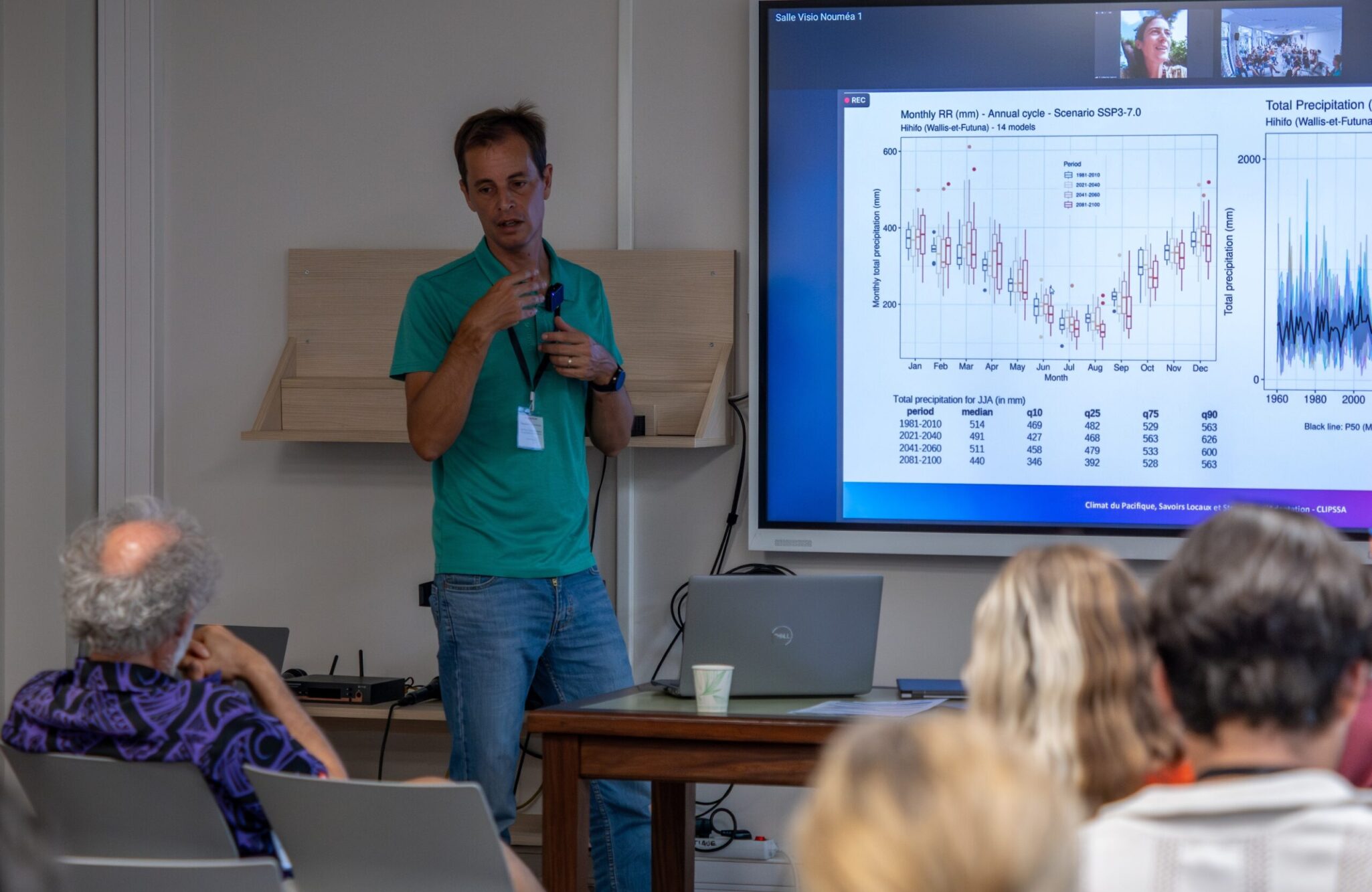

Accurate climate data is essential for forecasting agricultural yields and securing water resources in the South Pacific. Global climate models produced by the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, created in 1988 by the United Nations Environment Programme and the World Meteorological Organisation, which brings together 195 member states) are often too imprecise for the small islands of the South Pacific.

CLIPSSA refines this data using the ALADIN (20 km) and AROME (2.5 km) models to match the specific topography of the South Pacific islands. This is the downscaling methodology: integrating the specific characteristics of each island provides hyper-local accuracy, as these characteristics influence climate data. However, while there are certainties and grey areas if the rise in temperatures is confirmed, uncertainty remains about precipitation, requiring increased monitoring of extreme events, as presented by Dakéga RAGATOA, our researcher in modelling the impacts of climate change on agricultural systems.

Gildas GUIDIGAN (researcher and modeller) will link this data using the APSIMx model. This is an agricultural production system simulator developed to reproduce and analyse in detail the interactions between crops, climate, soil and agricultural management practices. This agronomic model will translate climate data into real impacts on food crops (yams, taro). This will make it possible to map the areas that could remain cultivable and those that might become vulnerable, thus providing concrete tools, adapted to the terrain, to support agricultural adaptation and sustainable water management strategies.

Adaptation by and for the territories of the South Pacific

For Séverine Bouard, geographer and panel moderator, adaptation cannot be one-size-fits-all; it reflects those who practise it. Each island has its own social and political organisation. And after five years of work, two observations have emerged: rich interdisciplinary collaboration has generated a huge amount of knowledge, but there are also gaps and challenges that show that data is still missing that is necessary for reliable and accurate modelling of food crops.